Special Sandstone of the Smithsonian "Castle"

|

In 1846, geologist David Dale Owen of New Harmony, Indiana, recommended a certain kind of sandstone for the construction of the Smithsonian Institution. There are three facts about this building material that make it very special:

(1) after quarrying, it changed color;

(2) after quarrying, it became much harder;

(3) it is no longer quarried.

|

|

|

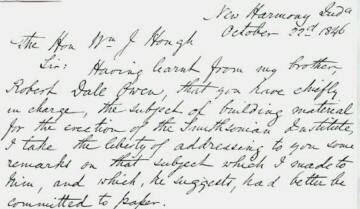

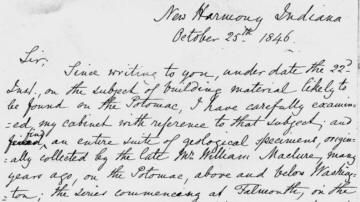

Two of Dr. Owen's letters repose in the Smithsonian Institution Archives, RU 7061, William Jervis Hough Papers. By permission, openings of the letters are shown here. They anticipate Dr. Owen's later recommendation of Seneca Creek Sandstone to the Smithsonian Building Committee, of which his brother, Congressman Robert Dale Owen, was the chairman. A few months later, Dr. Owen traveled to the Washington area and examined several quarries. |

|

He then submitted reports on 33 quarries and specimens. In the list, Seneca Creek Sandstone (for which the current geological name is Poolesville Member of Manassas Sandstone) was number 19. Owen's reports were published in

William Jones Rhees, editor, Smithsonian Institution: Journals,

Reports, Statistics, 589-90, 597, 604-9, 612-14, 664-67.

Excerpts from the report on pages 612-4, dated March 15, 1847, follow. Owen is writing here about a quarry on Bull Run, 23 miles up the Potomac River from Washington, D.C.

The beds which have been chiefly worked here are layers of a deep red color, (see specimen No. 18,) and layers of a purplish-gray, (No. 19,) which, by exposure, acquire a lighter and more pinky hue.

The latter is the rock most suitable for building purposes, its color being agreeable, and, in the opinion of men of good judgment and taste, appropriate for the Norman style of architecture. This rock possesses one property in particular which recommends it to the attention of builders. When first removed from the parent bed, it is comparatively soft, working freely before the chisel and hammer, and can even be cut with a knife; by exposure, it gradually indurates, and ultimately acquires a toughness and consistency that not only enables it to resist atmospheric vicissitudes, but even the most severe mechanical wear and tear. Abundant evidence of this is afforded in the buildings of the neighborhood...

Mr. Peter, on whose property this quarry is situated, has built a fine barn of these freestones. He assures me that there are stones in that barn 50 years old, which have been in three buildings. On one corner-stone, where the figures "1824" had been cut in that year by the point of a penknife, the rock now is so hard that it would soon turn the edge of a well-tempered tool.

... The singular property which the best quality of these freestones possesses, of hardening by exposure, is one of its most valuable characteristics; permitting it to be wrought at less expense than marble, and imparting to it a durability which increases with age. It has been a question, whether this property is due to iron in its composition, passing from a lower to a higher degree of oxidation, or to the presence of a sub-carbonate of lime, becoming gradually by exposure a carbonate of lime, and acting as a cement to the particles of silex. A minute chemical analysis would, no doubt, throw light on this matter. It might prove that this phenomenon depends on some other property not yet suggested.

(Recent efforts to determine whether an answer is known to Owen's question await fruition.)

In concluding this report, it may not be out of place briefly to advert to [two letters to Mr. Hough, mentioned above]. Mr. Hough will recollect that the second of these letters contains the following paragraph:

"It seems indeed strange, that, if really good and durable freestones are to be had on the canal or river above Washington, these should not already have been used for the public edifices there; but sufficient examples are to be found of the very best building material, having been overlooked through a long series of years, even in the vicinity of populous cities, for lack of minute and discriminating examination. My own firm belief is, that a durable sandstone, equal or nearly equal to that used in Trinity church [New York City], can be discovered in sufficient quantities in the vicinity of the Potomac or the canal."

It may afford some evidence of the confidence with which geological science may be appealed to in search of practical results, that an actual examination of one of the localitites...has fully confirmed all, and more than all, I had anticipated...

Specimen no. 19 in Owen's 1847 report is described in an appendix with these words: "Grayish-purple or pink variety of sandstone, Bull Run, near Seneca creek, Montgomery county, Maryland." It is of this stone that the Smithsonian Castle was soon thereafter constructed.

No one living has seen the Castle in its original color.

David Dale Owen

The Smithsonian Institution

New Harmony Scientists, Educators, Writers & Artists

Clark Kimberling Home Page