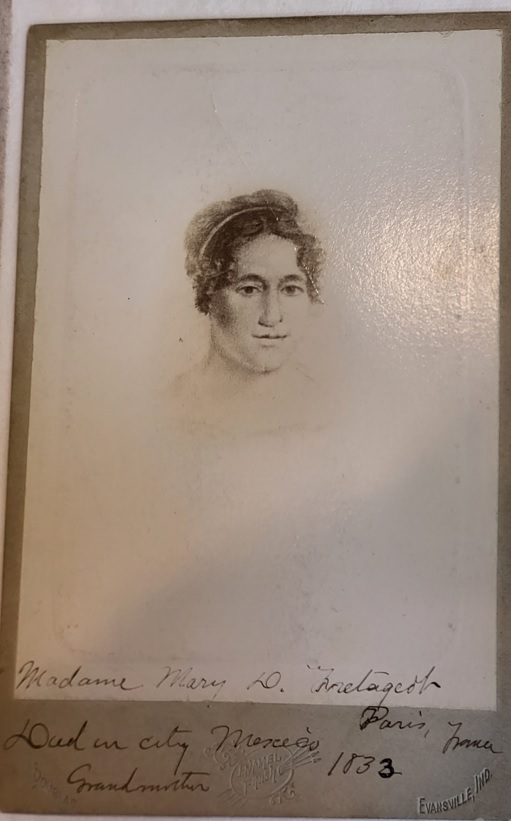

Marie Duclos Fretageot

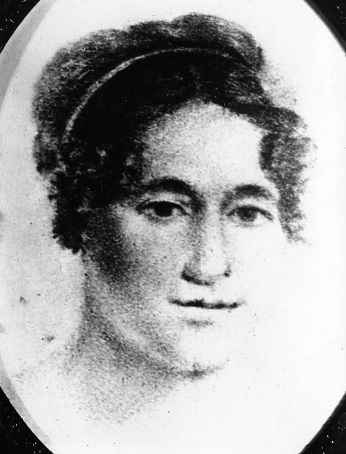

Madame Marie Duclos Fretageot.

Courtesy of Archives, University of Southern Indiana.

| Born | Marie Louise Duclos 3 September 1779 Lyon, France |

|---|---|

| Died | August, 1833 Mexico |

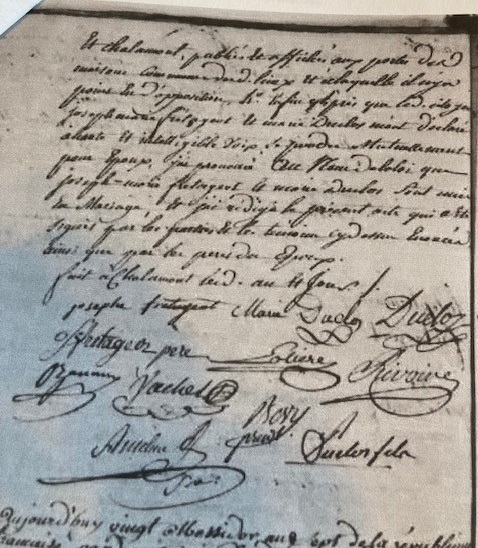

Marie Duclos was born in Lyon, France on 3 September 1779. Because this date precedes the usual published date by nearly four years, a detailed discussion is given below. Nearly twenty years later, on 18 June 1799 (a date missing in earlier accounts), she married Joseph Fretageot in Chalamont, France. Thereafter, she was referred to as Madame Fretageot, or simply Madame. Her son Achille Emery Fretageot was born in Paris on 24 October 1812, but researchers have considered the possibility that his father was not Joseph Fretageot.

Madame met William Maclure in Paris in 1819, not long after he had become President of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Like Maclure, she was interested in the principles of Robert Owen for social reform and education based on the methods of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi. With Maclure's support, Madame moved to Philadelphia in 1821, where she established a boarding school for girls. Indeed—as attested by two recently found letters Owen received from Madame—she was instrumental in persuading Maclure to join Owen in the establishing of a school-oriented social-reform community in New Harmony, Indiana.

During the winter of 1825-1826, both Maclure and Madame moved to New Harmony. For reasons of health, Maclure resided there only a short time, but Madame remained and managed his continuing financial support of science and education in New Harmony, against great odds. In 1831, she returned to Paris, and in February 1833, she joined Maclure in Mexico City. She died in Mexico in August, 1833.

Most of what is known about Madame is found in the first two sources listed here:

-

Madame Marie Fretageot: Communitarian Educator

, by Josephine Mirabella Elliott, Communal Societies 4 (1984), 167-182. - Partnership for Posterity: The Correspondence of William Maclure and Marie Duclos Fretageot, 1820-1833, edited, with Introduction, Notes, and Appendices, by Josephine Mirabella Elliott. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1994.

- Education and Reform at New Harmony: Correspondence of William Maclure and Marie Duclos Fretageot, 1820-1833, edited by Arthur E. Bestor, Jr., first published by the Indiana Historical Society, 1948, reprinted by Augustus M. Kelley Publishers, Clifton, New Jersery, 1973.

- The European Journals of William Maclure, edited, with Notes and Introduction, by John S. Doskey, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, 1988.

- Maclure of New Harmony: Scientist, Progressive Educator, Radical Philanthropist, by Leonard Warren , Indiana University Press, 2009.

- Eyewitness to Utopia: Scientific Conquest and Communal Settlement in C.-A. Lesueur's Sketches of the Frontier,, texts and photographs by Ritsert Bauke Rinsma, a Heiligon Publication, 2019. Sample pages: available from the Smithsonian Institution.

The main objective of this present account is to present relevant documents (birth records, military records, and letters) that provide information not found in the aforementioned references.

Courtesy of Purdue University Archives.

Unofficial and official records of birth and baptism

For many years, it has been thought that Madame was born on 31 August 1783 (e.g., Partners for Posterity, pages xxiv and 14). However, the official record in Lyon, France, shows that Marie Louise Duclos was born nearly four years earlier. The record (#301) can be viewed here: Cote 1GGe74, vue 497, in Archives municipales de Lyon, Ainay (Saint-Michel puis Saint-Martin) 03/01/1771-31/12/1780, Baptêmes Mariages. (For information about Ainay, see the Wikipedia articles Ainay, a part of Lyon and Basilica of Saint Martin, in Ainay).Marie, née d'avant-hier, fille de Pierre Duclos, maî tre menuisier, demeurant rue des Marronniers, et de Jeanne Farine, son épouse, a été baptisée par moi Vicaire soussigné, le cinq septembre mil sept-cent septante neuf. Le parrain a été Pierre Louis Balé, maî tre menuisier; la marraine, Demoiselle Marie Colombet, fille de Sieur Claude Colombet, maître sellier, qui ont signé avec le père: Pierre Duclos, Mari Colombet, Balé, François Colombet, Ragot, Dunand vicaire. Pour copie conforme.

Translation:

Marie, born the day before yesterday, daughter of Pierre Duclos, master carpenter, residing in rue des Marronniers, and of Jeanne Farine, his wife, was baptized by me, the undersigned Vicar, on the fifth day of September, one thousand seven hundred and seventy-nine. The godfather was Pierre Louis Balé, master carpenter; the godmother, Demoiselle Marie Colombet, daughter of Sieur Claude Colombet, master saddler, who signed with the father: Pierre Duclos, Mari Colombet, Balé, François Colombet, Ragot, Dunand vicar. Identical copy.

Madame's husband, Joseph-Marie Fretageot

Joseph-Marie Fretageot was born on 18 November 1774 in Bourg, Dordogne, Aquitane, France.

Although several publications state that Madame's husband was a colonel in Napoleon's army, French records indicate that he was instead a corporal — and a deserter. One such biographical dictionary is accessible online: Dictionaire des soldats de l'Ain 1789-1815), page 44. The entry in the dictionaire is quoted here:

Fretageot, Joseph. Demeurant dans le district de Bourg. Il ser comme caporal a la 1érc compagnie du 4c bataillon de l'Ain, matricule 111. It est présent lors de la revue d'Annecy, le 21 pluviôse an II. Admis à la 201c demi-brigard de bataille le 21 pluviôse an II. Il dèserte le 26 frimaire an IV.

Translation:

Fretageot, Joseph. Residing in the district of Bourg. He served as corporal in the 1st company of the 4th battalion of Ain, number 111. He is present during the Annecy review, on 21 pluvios Year II. Admitted to the 201st deim-brigade of battle on 21 pluviose Year 2. He deserted on 26 frimaire Year IV.

A few notes may be helpful: "pluviose" is 5th month of the French Republican Calendar (Jan and Feb - roughly Jan 21 to Feb 19); "frimaire" (3rd month of the French Republican Calendar [1793-1805], roughly Nov 22 to Dec 21. Years II and IV were essentially 1793 and 1795. (For details, see French Republican calendar.) A search of the 47 pages of the Dictionaire for names beginning with "F" shows that the word dèserte or an equivalent occurs 82 times, indicating that desertion was not uncommon. In some cases the deserter paid a fine or was returned to service.

Published here perhaps for the first time is the date of Joseph's death: 16 December 1846. The death certificate can be viewed on the right side of page 98 in Archives départementales du Val-de-Marne, Gentilly, Décè).

Madame's schools in Philadelphia

It is well known that Madame operated a boarding school for girls in her home during 1821-1825 in Philadelphia, first at 20 Filbert Street, and then on Ridge Road. Doskey, in reference (4) above, page xxxviii, indicates that Madame had already run a boarding school for girls in Philadelphia before 1821. On page 687, Doskey writes, "There is evidence to the effect that she had been in America before 1821 because she seems to have already known many of Maclure's friends, including Thomas Say and Charles Alexandre Lesueur. Maclure himself stated in one of his letters (dated 4 December 1821, sent from Madrid, Spain) that she formerly kept a boarding school in Philadelphia (see Maclure-Silliman Correspondence, Yale University Library)." The letter is presently classified at Yale with Call Number MS450, Box 20, Series II, in Reading Room MSS. The passage Doskey refers to occurs on page 3:

...Madame Fretageot a Lady that formerly kept a boarding school in Phila[delphia] has returned to that town with all the latest inventions for facilitating the acquiring of all usefull knowledge which has been much perfected in parts of Europe within this last few years such as mecanizms for teaching arithmetic and reducing all kind of mathematics within the comprehension of very young children, teaching geography and astronomy by globes and ingeneous inventions for rendering all the ideas clear by tangible and appropriated mechanizms a new way of learning music in as many months as they used formerly to take years... Madame Fretageot is every way capable of teaching...necessary parts of education and if any of your friends have any young girls that they wish to be educated have no doubt that they will be satisfied with her.

This account raises questions about Madame's life prior to 1819, when she was already forty years old. See below, "Questions for further research."

Item 40036, Courtesy of Muséum d'histoire naturelle, Le Havre, France.

Item 40037, Courtesy of Muséum d'histoire naturelle, Le Havre, France.

Item 40038, Courtesy of Muséum d'histoire naturelle, Le Havre, France.

Pestalozzian education

As editor of The American Journal of Science and Arts, Benjamin Silliman asked Maclure to write on the subject of Pestalozzian education. Excerpts of Maclure's letter dated August 19, 1825, were published in the October 1825 issue of the Journal. Portions of the letter are quoted here.

Madam Fretageot's school has been established here 4 years next October, has 32 pupils, as many as she can take, and several are waiting for vacancies; she has already completed the education of some, whose parents thought them sufficiently instructed in all useful and necessary information.

Mr. Phiquepal began his school a few months ago, has 18 pupils, and will very soon have as many as he wishes to take; as the method requires more constant attention of the part of the instructor than that of the old schools, particularly at first; as the greatest part of the scholars have been treated differently by previous education, and have got habits that must be changed before they can be effectually benefited by the system. It would be necessary, to reap the full advantage of the method, that the children should be sent before they were at any school, except being taught by the mother, who would be aided much by a small book published by Pestalozzi, called the Mother's Manual.

I have seen nothing printed about the system except Neef' Sketch, which is all sold...

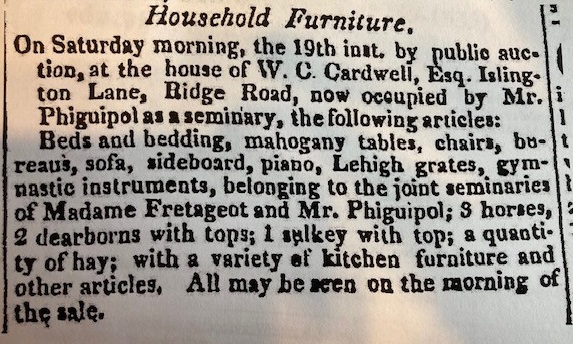

Shown here is a notice in a Philadelphia newspaper, indicating Macure's affiliation with Pestalozzian teacher William S. Phiquipal (whose full French name was Guillaume Sylvan Casimir Phiquepal d'Arusmont).

For descriptions of Pestalozzian education and its influence in Europe, America, and New Harmony, see Hermann Krüsi, Pestalozzi: His Life, Work, and Influence and Gerald Lee Gutek, Joseph Neef: The Americanization of Pestalozzianism, The University of Alabama Press, 1978.

Recently found letters from Madame to Robert Owen

In a letter dated 19 September 1824, William Maclure wrote to B. Silliman, "Mr. Robert Owen of New Lanarck [Lanark] has just decided to make the United States the fate of his future experiments on the facility, utility, satisfaction..." Here, Maclure gives no hint of his forthcoming interest in joining Owen's experiments. Possibly Maclure would not have joined Owen had Madame not influenced him to do so. In addition to correspondence documented in Elliott's Partnership for Posterity, two further letters revealing that influence were recently discovered.

A letter dated 15 February 1825 from Madame Fretageot to Robert Owen appears not to have been previously published. A copy is shown here with transliteration.

Courtesy of The Co-operative Heritage Trust.

Well, my friend, Mr. Phiquepal will leave here the 18th and arrive by you the 20th. I regret very much that such talkers would be so far from my ear but I will take my turn at the end of April— it is to say at your return from the Western countries. But as it is necessary that I should be informed of the means that are to be found in your new Empire for to do good when still there be a number of children to be brought up and the means of instruction have they been provided for or when will they be provided for? What has been made for to assure the complete execution of the plan? Or could you not give me a general idea of the advantages for the new settlers? I have a thousand more questions to make but I imagine you will answer them in your conversations with Mr Phiquepal or you will write them to me. My desire in asking those questions is that I may be able to give to Mr. Maclure as many details as possible on your interesting new world. For my part I dare not to say that I am quite your proselyte. Are you not very proud of it?

Mr. Maclure, for whom I have the greatest esteem, being informed by you and by me, will join me in my opinion and I consider it would be a great acquisition. He will be here in April. You must meet him at his arrival. Tell me, are you returning in England next Spring? It seems that I heard something about it.

I must finish here agree my sincere affection. M. D. Fretageot; February 15th 1825.

A few days later, Madame sent Robert Owen a second letter, which also appears not to have been previously published.

Courtesy of The Co-operative Heritage Trust.

My Dear friend, I could not expect an answer so well calculated to please me as your promise to come before you return to Harmony. Indeed, I am delighted with the idea that I will hear from you all that I wish to know. It is essential that we could inform Mr Maclure before he leaves France because he would collect every thing proper for the new Colony. As I have already spoken much on the matter specially that you was to return in May here. I engaged him much to hasten his departure in order to meet with you. But as you will not be here before June, he will have more time if our letters reach him in time. We have a rooming prepared for you at Mr Phiquepal that we may enjoy your society exclusively for two words to inform us of the day of your arrival.

Must I tell you to make haste I would indeed if it could have any effect.

I remain with much affection yours, M. D. Fretageot; February 26th 1825.

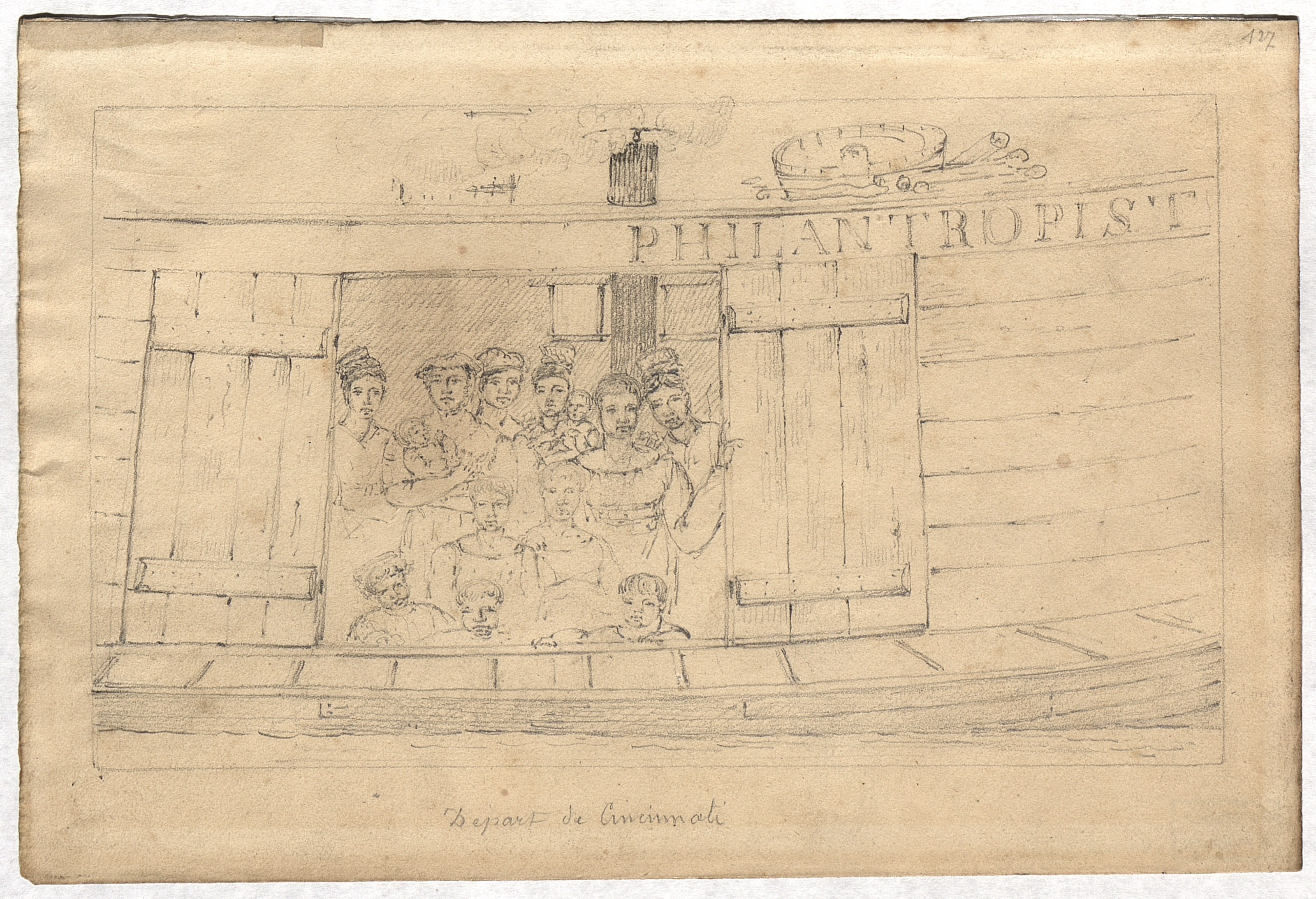

From Philadelphia to New Harmony on the Philanthropist

The author of Robert Dale Owen's Travel Journal 1825-1826, published as To Holland and to New Harmony, edited by Josephine M. Elliott (Indiana Historical Society Publications, v. 23, no. 4, Indianapolis, 1969), provides insights into Madame's character during the journey from Pennsylvania to New Harmony. Most of the journey was aboard the Philanthropist, an 85-foot long keelboat nicknamed the Boatload of Knowledge by Robert Owen, father of Robert Dale Owen; see See Donald E. Pitzer, The Original Boatload of Knowledge Down the Ohio River: William Maclure's and Robert Owen's Transfer of Science and Education to the Midwest, 1825-1826. The twenty-four year old Owen wrote some of his observations in German, and these are quoted here along with Elliott's translations.

Sunday, 13 November, 1825, in Philadelphia. Walked out with Dr. Price to see Madame Fretageot, where we found Leseuer [Lesueur], Maclure, Mr. & Mrs. Lewis and some young ladies, Mrs. F's pupils. M. R. ist eine hoechst sonderbare Frau, scheint ein wahres maennliches Gemueth zu haben, ud [und] ich glaubte sie wird in Harmonie ihren Platz aufs aller beste fuellen; doch davon mehr nachher. [Mme F. is a highly remarkable woman, seems to have a truly mannish disposition and I believe she is going to fill her place in Harmony at her very best. But more of this later.]

10 December, in Economy (on the Ohio), Pennsylvania. Mme read aloud to us part of Fourier's work in the evening: it is a strange and most original production, containing may excellent ideas, but mixed up with much which is, I think not practical. [See Fourierism, where it is noted that "In contrast to the thoroughly secular communitarianism of his contemporary Robert Owen (1771-1858), Charles Fourier's thinking starts from a presumption of the existence of God and a divine social order on Earth in accordance with the will of God."]

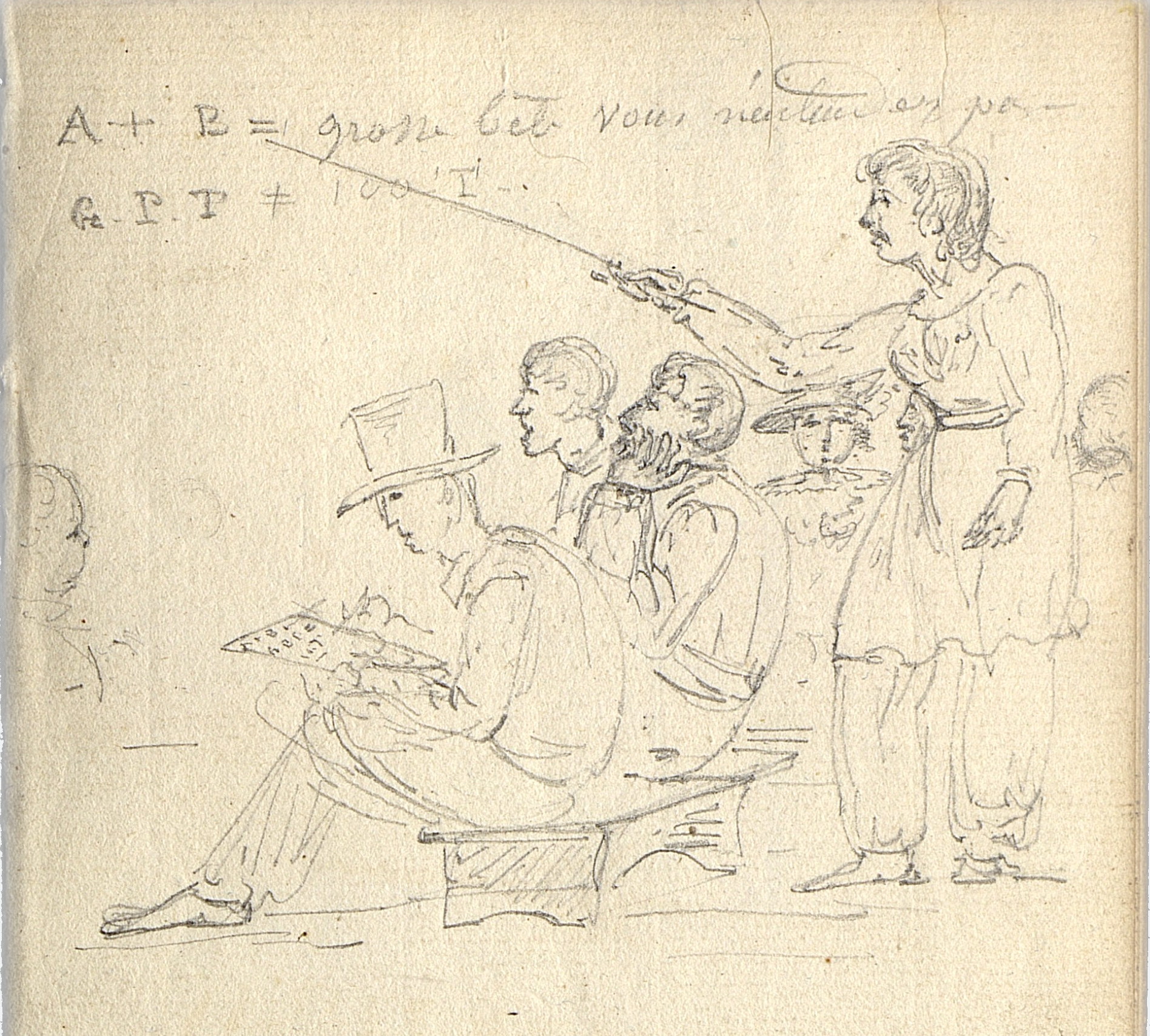

Drawn by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, 31 December 1825.

Item 46 050, Courtesy of Muséum d'histoire naturelle, Le Havre, France.

16 December, in Safe Harbor (on the Ohio, 15 miles below Economy, and 8 miles above Beaver, during a time that the Philanthropist was ice-bound). Die Frau F ist wahr ein ausgezeichnetes Weib in jeder Hinsicht. Die Art wie sie den Herrn P. [Phiquepal] heute bei seiner Krankheit handelte war mir ein starker Beweis ihrer Geistestaerke ud ihrer Vernunft. [Mme F is an excellent woman in every respect. The manner in which she acted today for Mr. P in his illness was for me a strong indication of her intelligence and her good sense.]

17 December, in Safe Harbor. Hatte ein sonderbares Gespraech mit der Frau F. ueber unsere Familienverhaelnisse. [Today I had a curious conversation with Mrs. F. about our family affairs.]

29 December. Hatte ein langes Gespraech mit der Frau F. ueber meine Verhaeltnisse zo hause. [Had a long conversation with Mme F. about my situtation at home.] Owen gives no further reference to the Verhaeltnisse in his notes of 17 and 29 December; Elliott suggests (p. 178) that the subject was his love for the young Margaret he has left behind. This suggestion is supported by a description of Margaret in Richard William Leopold's biography Robert Dale Owen, Octagon Books, New York, 1969. Leopold writes that Margaret had become "a member of the Owen household and was henceforth treated as one of the family" in Braxfield, Scotland, in March 1823, and that when he returned there in the summer of 1827 he found her "as charming as ever" and considered marrying her.

29 December (continued). From a description of Parisian manners which Madame gave me this evening, I am induced to think that many parts of them are most worthy of imitation amongst ourselves; for instance the perfect freedom from restraint or ceremony which characterizes their intercourse with one another. And their disposition to make the best of every situation and enjoy without excess the present moment: then again their civility even to perfect strangers and their easy politeness to one another.

Saturday, 7 January 1826 (two days before leaving Safe Harbor, where they had been detained by ice for four weeks). In the evening Virginia Dupalais [age 21] arrived from Beaver whither her brother [Victor] and Leseur [Lesueur] had gone to meet her.

8 January 1826. Die Dame die gestern ankahm scheint ganz ud gar sich unerer Lebensweise fuegen zu wollen ud haelt sich wirkl[ich] rech brav. [The lady who arrived yesterday (Virginia Dupalais) seems to want to fit entirely into our way of life and conducts herself really quite bravely.]

Virginia Dupalais, first on left; Madame Fretageot, second on right.

Item 41 089-1, Courtesy of Muséum d'histoire naturelle, Le Havre, France.

Impressions of Karl Bernhard, Duke of Saxe-Weimar

In his Travels through North America, during the year 1825 and 1826, vol. II, pp. 431-436, His Highness portrays Virginia Dupalais and Madame in a manner not found elsewhere:

In the evening [of 16 April 1826] I paid visits to some ladies, and witnessed philosophy and love of equality put to the severest trial with one of them. She is named Virginia, from Philadelphia; is very young and pretty, was delicately brought up, and appears to have taken refuge here on account of an unhappy attachment. While she was singing and playing very well on the piano forte, she was told that the milking of the cows was her duty, and that they were waiting unmilked. Almost in tears, she betook herself to this servile employment, deprecating the new social system, and its so much prized equality.

After the cows were milked, in doing which the poor girl was trod on by one, and daubed by another, I joined an aquatic party with the young ladies and some young philosophers, in a very good boat upon the inundated meadows of the Wabash. The evening was beautiful moonlight, and the air very mild; the beautiful Miss Virginia forgot her stable sufferings, and regaled us with her sweet voice. Somewhat later we collected together in the house No. 2, appointed for a school-house, where all the young ladies and gentlemen of quality assembled. In spite of the equality so much recommended, this class of persons will not mix with the common sort, and I believe that all the well brought up members are disgusted, and will soon abandon the society. [The Utopian society was indeed abandoned during 1827.]

[A few days later] In the evening I visited Mr. M'Clure and Madam Fretageot, living in the same house [No. 4, where the duke was invited to dinner]. She is a French-woman, who formerly kept a boarding-school in Philadelphia, and is called mother by all the young girls here. The handsomest and most polished of the female world here, Miss Lucia Saistare [Lucy Sistare, who secretly married Thomas Say in New Harmony a few months later] and Miss Virginia, were under her [Madame's] care. The cows were milked this evening when I came in, and therefore we could hear their performance on the piano forte, and their charming voices in peace and quiet. Later in the evening we went to the kitchen of No. 3, where there was a ball. The young ladies of the better class kept themselves in a corner under Madam Fretageot's protection, and formed a little aristocratical club.

[The next evening, the duke] visited Mr. M'Clure, and I entertained myself for an hour with the instructive conversation of this interesting old gentleman. Madam Fretageot, who appears to have considerable influence over Mr. M'Clure took an animated share in our discourse. [Shortly before leaving New Harmony, the duke continues --] I passed the evening with the amiable Mr. M'Clure and Madam Fretageot, and became acquined through them with a French artist, Mons. Lesueur, calling himself uncle of Miss Virginia. [Elsewhere it is written that Lesueur was not really Virginia's uncle, but that he was in some sense responsible for the well-being of both Virginia and Lucy.]

From Diary and Recollections of Victor Colin Duclos

The information was copied from the original manuscript by Mrs. Nora C., Fretageot and published in Indiana as Seen by Early Travelers (Indiana Historical Commission, Indianapolis, 1916).

I am a native of France and was born in Paris, May 22, 1818. I left there in the early part of the year 1823 with my aunt, Madam Marie D. Fretageot, to attend a School of Industry established by Mr. William Maclure in Philadelphia, Pa. We started from Havre in a sailing vessel in March, 1823, and were six weeks on the voyage. On board this vessel, who intended to make this school their home, were Madam Fretageot, her son Achilles E. Fretagerot, a Swiss named Balthazar, Charles A. Lesueur, two French students, my brother, Peter L. Duclos, myself and several others. We arrived in New York in May, and went to Philadelphia in June. The school house was situated on the Schuylkill road about one mile from the city. It was a large fine brick building with a very large arched door in the centre. Surrounding the school building, were the most beautiful pleasure ground imaginable. This was William Maclure's "School of Industry."

It appears that Duclos, writing when elderly, was confused on some points, as has been noted elsewhere. In particular, Maclure did not have a "School of Industry" in Philadelphia. He had enabled Joseph Neef, a Pestalozzian teacher, to operate a school for boys in Falls of Schuykill, near Philadelphia, beginning in 1809, but before 1813, Neef had moved the school to Village Green in Chester County, Pennsylvania, and from there, Neef moved to Kentucky, where he took up farming. In 1826, he moved to New Harmony, Indiana. For details, see Ruth Lee Koch's dissertation.

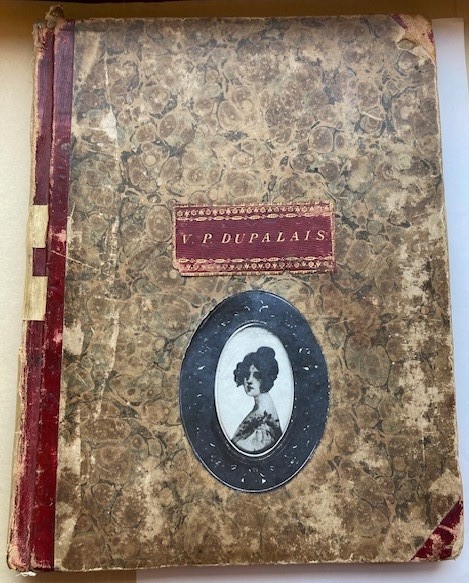

Virginia Dupalais (Twigg).

Courtesy of Archives, University of Southern Indiana.

Courtesy of Archives, University of Southern Indiana.

Virginia Dupalais

Recall from Karl Berhard's impressions, quote above, that Virginia Dupalis and Lucy Sistare were regarded as "young ladies of the better class...under Madam Fretageot's protection...a little aristocratical club." The life and work of Lucy Sistare--soon to become Mrs. Thomas Say--has been documented elsewhere (e.g., Lucy Say). On the other hand, attempts to account for Virginia's family and upbringing are still ongoing.Records indicate that Virginia was an assistant to Madame in her Philadelphia boarding school for girls and that Virginia and her younger brothers, Victor and Andre [acute over e], were wards of Charles Alexandre Lesueur; indeed they resided with him in his house in New Harmony. Virginia called Lesueur her uncle, but only as a term of endearment. An interesting summary of what is known and what remains unknown about the Dupalais family and Lesueur is given by Bauke Ritsert Rinsma in Eyewitness to Utopia [title in italics], Heiligon Publications, 2019.

No official record seems to exist for Viginia's birth, said to be in 1804 in Philadelphia, or the birth of her brother Victor, who is said to have been seven years old in 1825. Allegedly, Virginia's parents were Pierre Gueymard du Palais and Marie Mignot du Palais. (Possibly the only published record of Virginia's mother's name is in The Evansville Press, 3 March 1935, page 20, based on information from Virginia's granddaughter, also named Virginia.)

The man named as Virginia's father in Dupalais records was an officier among several thousand French soldiers under Compte Rochambeau, who assisted George Washington in the American Revolutionary War. According to a French military record, P. G. du Palais was born in 1741, which seems too early for him to have fathered Virginia and her younger brothers. (See page 270 in Combattants francais de la guerre americaine 1778-1783.) Moreover, according to records found by French geneologist Sophie Boudarel, P. G. du Palais's widow died in 1843, and her posthumous inventory indicates that there was only one living child, the sole heiress.

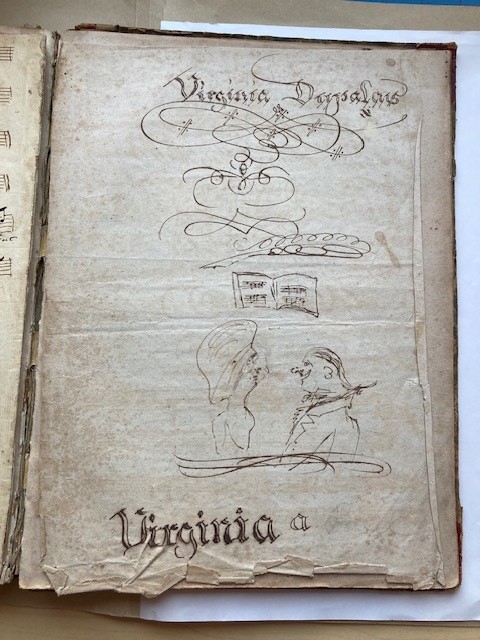

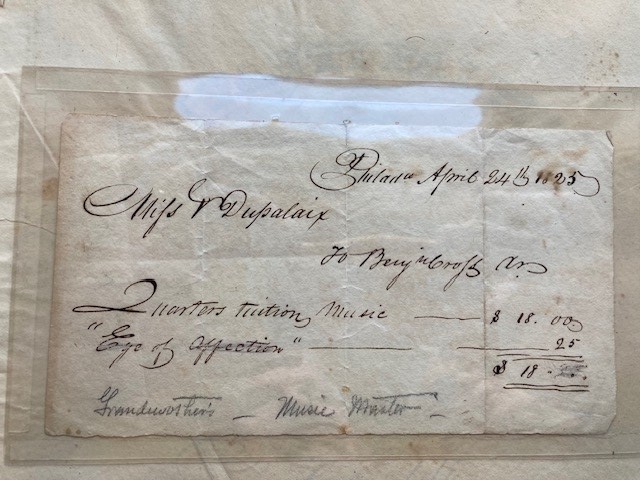

The mysteries surrounding Virginia's parentage are compounded with several problems: (1) unknown death records for her parents; (2) unknown records in Philadelphia of the Dupalais residence or activities there; (3) reliability of records pertaining to Virginia's musical training. Fortunately, she kept sheet music from several different publishers; these are bound together in three volumes, which, in the Working Men's Institute, include a few images and written biographical information, pictured here.

In 1828, Virginia married William Augustus Twigg, who became one of the leading citizens of New Harmony. According to the "W. A. Twigg Papers" in the Indiana Historical Society Library, based on notes written by Virginia's granddaughter, Virginia was a daughter of "Pierre Alexandre Poulard de Guemar DuPalais, a Capitaine commandant in the French forces of Compte Rochambeau." The notes indicate that "Virginia's musical training was exceptional. She played piano, sang in Spanish, Italian, French and English, and her own piano, many music books, etc., came with her on the Boat [Philathropist]."

The previously mentioned article in The Evansville Press notes that the instrument was made by the Clementi Company in England. It is claimed elsehwere that Madame's piano was also on the Philanthropist. A third image of such an instrument was sketched in New Harmony by Lesueur, but a curator of an early piano museum has advised that Lesueur's portrayal is an artist's idealized representation.

Virginia's music volumes include a note that Virginia was a pupil of Manuel Garcia. However, it appears that Garcia's places of residence during the years that Virginia was taking music lessons did not include Philadelphia. See Manuel Garcia Biography.

In New Harmony, Virginia taught music in Madame's primary school. In 1828, she married William Augustus Twigg, who became one of the leading ciziens of New Harmony. The couple had five children. Virginia died in New Harmony in 1864.

Both Madame Fretageot and Virginia Dupalais are described in the context of the musical life of New Harmony during 1826-1832 in Melanie Lynn Zeck's Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Chicago, Department of Music: Dissertation.